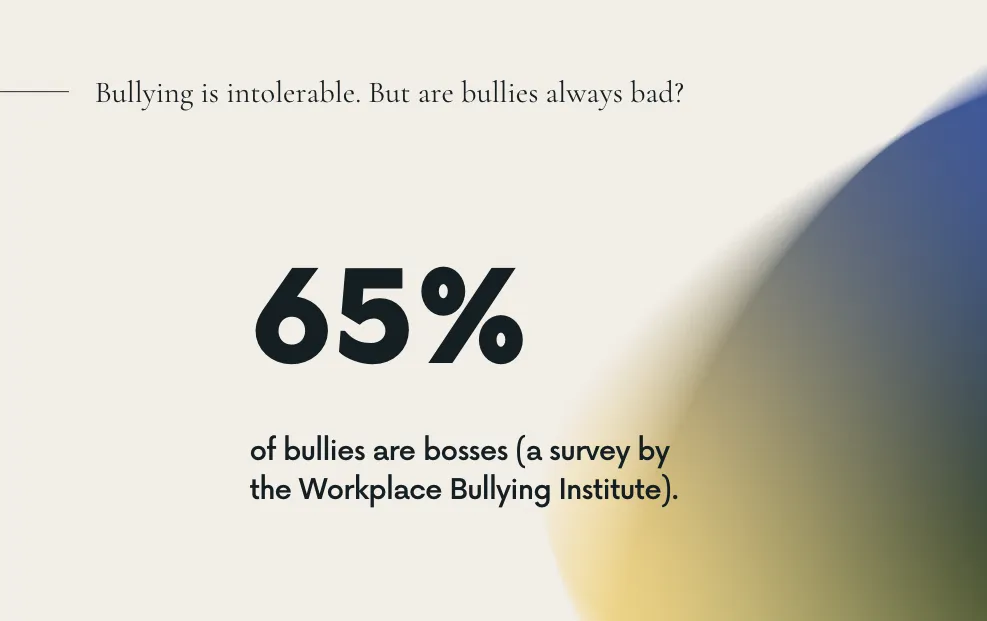

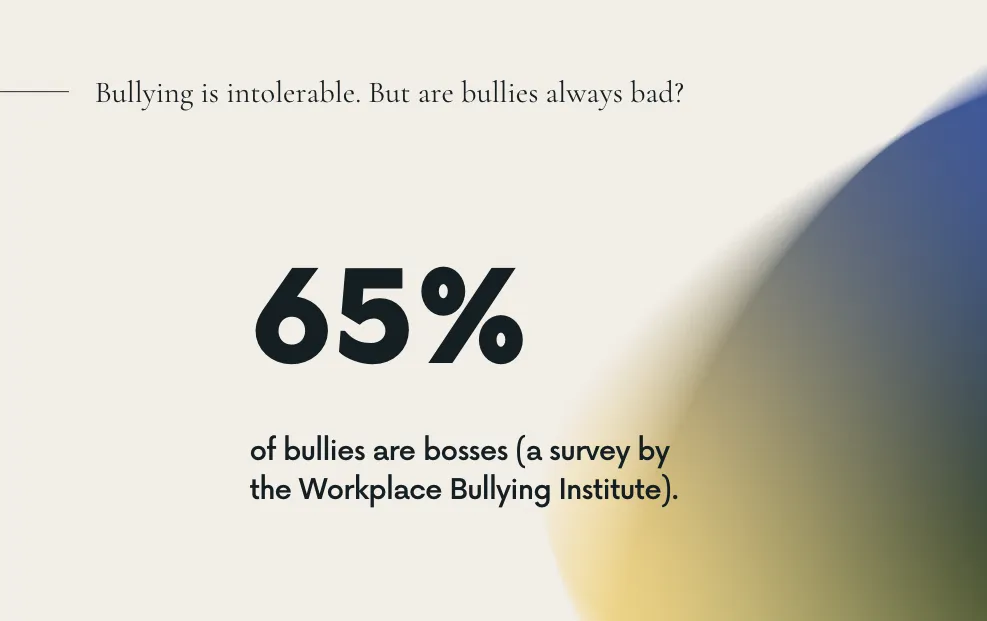

Bullying is intolerable. But are bullies always bad?

When fear festers, bullying often follows

.png)

“Bullies have a scarcity mindset. They believe the world is fundamentally hostile. They tend to be overplaced to their actual abilities. They have this deep, deep hunger for status and recognition.” - Amy Cuddy

In the first year, I was quite good – although my boss didn’t share that opinion.

In the second year, he may have had a point.

By the third year, he was right: I was sh*t at my job.

The swearing and public dressing-downs, the interminable caustic criticism, the brutal humiliations – they blitzed my self-worth. I was left second-guessing what he might want, just to avoid being shouted at. Clear, assertive decisions gave way to a hesitant, nervous, foggy paralysis. I became a pale imitation of the bright, imaginative, emotionally intelligent man who had joined a few years earlier.

When work follows you home

The anxiety didn’t stay at the office. It entered other aspects of my life, as if by osmosis. My marriage suffered and then failed. My health deteriorated, mentally and physically, through a stress-related autoimmune condition. Friendships frayed. Life and work became things to be joylessly tolerated.

Several colleagues suffered the same onslaught, but that was little consolation. My complaints to HR only amplified my sense of victimhood. A defensive HR manager implied the fault lay with me – that I should toughen up.

The sense of threat was constant. Cortisol and adrenaline perpetually flooded my system, until my sympathetic stress response shifted from fight-or-flight to the most extreme option: freeze.

In the animal kingdom, freezing is the last resort of a creature caught by a predator – playing dead in the hope the mauling will subside. Humans can do the same, shutting down unconsciously when the nervous system decides it’s the only way to stay safe.

Even now, almost two decades on, the shame, inadequacy and embarrassment aren’t entirely gone. I hesitate to share this story with people who know me now as confident, calm and successful – or with those who knew me then.

That’s what bullying does. It diminishes us.

The easy story, and the harder one

It is seductive to join the zeitgeist that bullying must never be tolerated. And I agree: bullying is unacceptable in any progressive organisation and must be tackled with clarity and unambiguous purpose.

But here’s the harder question: are bullies always the “toxic” villains we imagine – or sometimes people in over their heads, lashing out from fear?

I never had a proper conversation with “my” bully. He had been promoted beyond his level by a CEO impressed by his functional expertise. Once in the role, I suspect his fear of failure, his imposter syndrome, and his anxiety about inadequacy triggered his fight response.

Nowadays, I can nurture compassion for leaders facing this kind of difficulty – even for him.

When styles collide

He got on marvellously with people he rated and who shared his approach. I wasn’t one of them.

He was detail-oriented; I was more abstract (and less thorough). He had a command-and-control style; I leaned toward collaboration (and indecision). He was certain; I was curious (and hence slower).

In a frenetically competitive industry, he wasn’t interested in diversity of thought. He needed people to do what he told them, and do it quickly. Members of his team who questioned directives were, to him, exasperating. We were a threat – and thus, literally, infuriating.

The fury my colleagues and I triggered manifested in constant aggression, which only made it harder for us to deliver what he wanted. From his perspective, I was the problem. From mine, he was. When things are out of kilter, we often behave in ways that get us more of what we don’t want.

Realising my own capacity

With the help of some wonderful people, I eventually escaped and began to re-find myself. A few years later, I was leading a big department through a major change programme.

Two of my team resisted the new vision. I felt the same exasperation my old boss must have felt with me. Did they feel bullied? I can’t say with certainty that they didn’t. I hope I treated them with respect and care, but I was stressed and so were they. Stress narrows perception. That thought still makes me uneasy.

Bullies are rare. Fear is common.

There are people who want to make others’ lives miserable for the sake of it. But in my experience, they are relatively rare.

Much more often, bullying is a compulsive response to fear: the fear of failing, of losing authority, of being exposed as inadequate. Seniority exposes lifelong insecurities, threatening self-image and reputation. Sometimes, the grasp for power, agency, and superiority emerges as persecution of others.

Managing teams can be lonely and stressful. Failing to command respect, failing to feel followership, can lead to an aggressive response. Which can quickly spiral into bullying.

What organisations must do

Bullying must be addressed with clarity and urgency. But simply banishing the “bullies” after accusations surface is too little, too late.

Leaders need development and care long before they reach breaking point – before their own pressure begins to break others. Senior leadership and HR must reflect on how unsupported, un-self-aware, insecure people end up in roles where fear hardens into aggression.

Equally, they must nurture those managers willing to confront their insecurities – through reflection, coaching, or leadership training. Organisations must recruit, promote and support leaders who work with their vulnerabilities rather than masking them with injurious power.

When we uphold this duty of care, we manage bullying at its source, instead of waiting until individuals – and the wider workplace – have reached boiling point.

SPEAKERS

“Bullies have a scarcity mindset. They believe the world is fundamentally hostile. They tend to be overplaced to their actual abilities. They have this deep, deep hunger for status and recognition.” - Amy Cuddy

In the first year, I was quite good – although my boss didn’t share that opinion.

In the second year, he may have had a point.

By the third year, he was right: I was sh*t at my job.

The swearing and public dressing-downs, the interminable caustic criticism, the brutal humiliations – they blitzed my self-worth. I was left second-guessing what he might want, just to avoid being shouted at. Clear, assertive decisions gave way to a hesitant, nervous, foggy paralysis. I became a pale imitation of the bright, imaginative, emotionally intelligent man who had joined a few years earlier.

When work follows you home

The anxiety didn’t stay at the office. It entered other aspects of my life, as if by osmosis. My marriage suffered and then failed. My health deteriorated, mentally and physically, through a stress-related autoimmune condition. Friendships frayed. Life and work became things to be joylessly tolerated.

Several colleagues suffered the same onslaught, but that was little consolation. My complaints to HR only amplified my sense of victimhood. A defensive HR manager implied the fault lay with me – that I should toughen up.

The sense of threat was constant. Cortisol and adrenaline perpetually flooded my system, until my sympathetic stress response shifted from fight-or-flight to the most extreme option: freeze.

In the animal kingdom, freezing is the last resort of a creature caught by a predator – playing dead in the hope the mauling will subside. Humans can do the same, shutting down unconsciously when the nervous system decides it’s the only way to stay safe.

Even now, almost two decades on, the shame, inadequacy and embarrassment aren’t entirely gone. I hesitate to share this story with people who know me now as confident, calm and successful – or with those who knew me then.

That’s what bullying does. It diminishes us.

The easy story, and the harder one

It is seductive to join the zeitgeist that bullying must never be tolerated. And I agree: bullying is unacceptable in any progressive organisation and must be tackled with clarity and unambiguous purpose.

But here’s the harder question: are bullies always the “toxic” villains we imagine – or sometimes people in over their heads, lashing out from fear?

I never had a proper conversation with “my” bully. He had been promoted beyond his level by a CEO impressed by his functional expertise. Once in the role, I suspect his fear of failure, his imposter syndrome, and his anxiety about inadequacy triggered his fight response.

Nowadays, I can nurture compassion for leaders facing this kind of difficulty – even for him.

When styles collide

He got on marvellously with people he rated and who shared his approach. I wasn’t one of them.

He was detail-oriented; I was more abstract (and less thorough). He had a command-and-control style; I leaned toward collaboration (and indecision). He was certain; I was curious (and hence slower).

In a frenetically competitive industry, he wasn’t interested in diversity of thought. He needed people to do what he told them, and do it quickly. Members of his team who questioned directives were, to him, exasperating. We were a threat – and thus, literally, infuriating.

The fury my colleagues and I triggered manifested in constant aggression, which only made it harder for us to deliver what he wanted. From his perspective, I was the problem. From mine, he was. When things are out of kilter, we often behave in ways that get us more of what we don’t want.

Realising my own capacity

With the help of some wonderful people, I eventually escaped and began to re-find myself. A few years later, I was leading a big department through a major change programme.

Two of my team resisted the new vision. I felt the same exasperation my old boss must have felt with me. Did they feel bullied? I can’t say with certainty that they didn’t. I hope I treated them with respect and care, but I was stressed and so were they. Stress narrows perception. That thought still makes me uneasy.

Bullies are rare. Fear is common.

There are people who want to make others’ lives miserable for the sake of it. But in my experience, they are relatively rare.

Much more often, bullying is a compulsive response to fear: the fear of failing, of losing authority, of being exposed as inadequate. Seniority exposes lifelong insecurities, threatening self-image and reputation. Sometimes, the grasp for power, agency, and superiority emerges as persecution of others.

Managing teams can be lonely and stressful. Failing to command respect, failing to feel followership, can lead to an aggressive response. Which can quickly spiral into bullying.

What organisations must do

Bullying must be addressed with clarity and urgency. But simply banishing the “bullies” after accusations surface is too little, too late.

Leaders need development and care long before they reach breaking point – before their own pressure begins to break others. Senior leadership and HR must reflect on how unsupported, un-self-aware, insecure people end up in roles where fear hardens into aggression.

Equally, they must nurture those managers willing to confront their insecurities – through reflection, coaching, or leadership training. Organisations must recruit, promote and support leaders who work with their vulnerabilities rather than masking them with injurious power.

When we uphold this duty of care, we manage bullying at its source, instead of waiting until individuals – and the wider workplace – have reached boiling point.

.png)

.png)